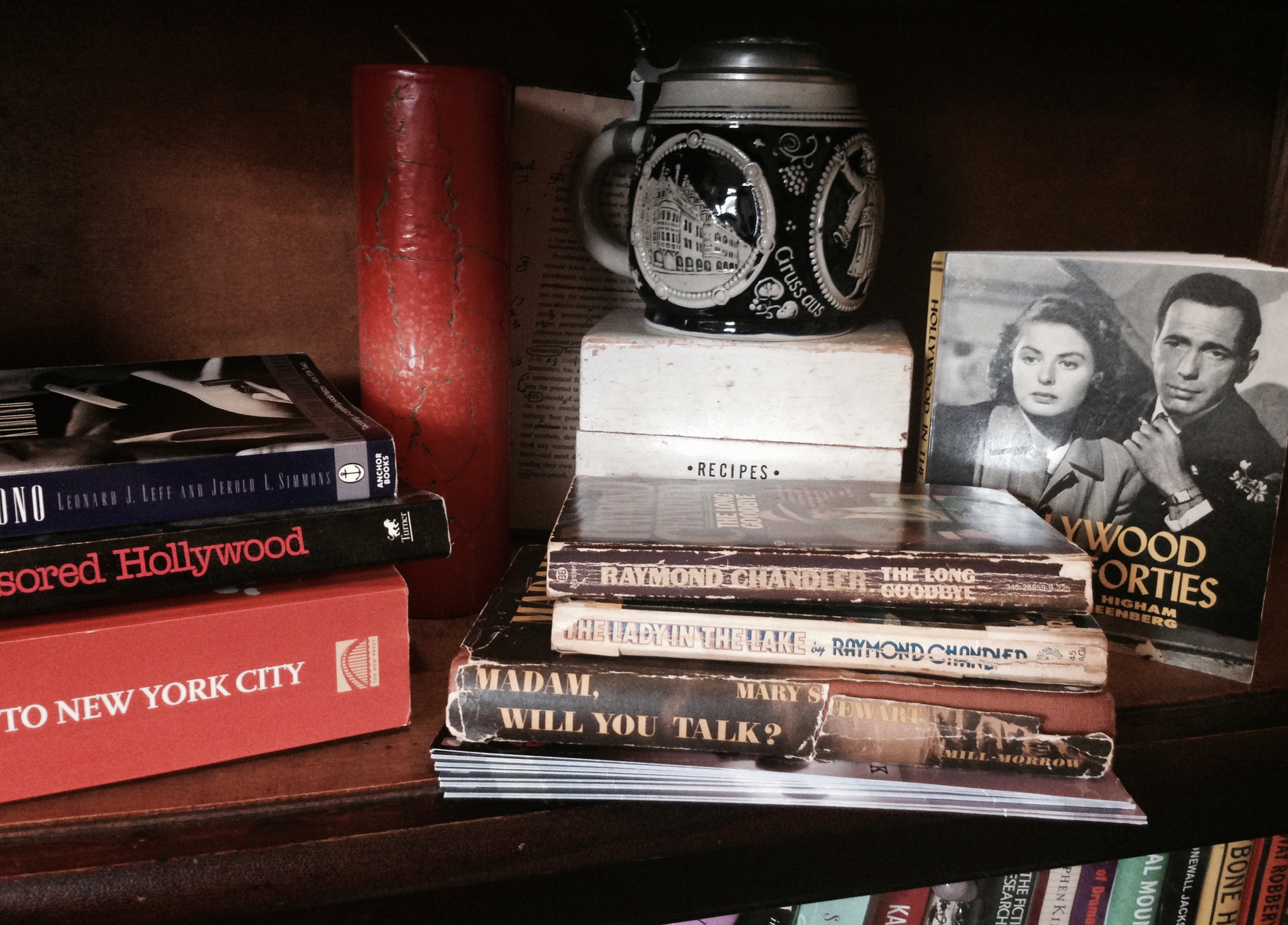

How did I end up in the 1940s? Theft. Well, more precisely, it was borrowing that turned out to be permanent.

My life in crime began by filching Raymond Chandler paperbacks from my father’s bookcase in junior high and secreting them among my Mary Stewarts, Daphne du Mauriers and Victoria Holts. I still have my original copy of Stewart’s Madame, Will You Talk?, shown here with two of the Chandler great grandchildren.

Those early years were seasoned liberally with juvenile delinquency: tardy term papers and school days skipped altogether – I may hold the world’s record for staying home with a sore throat – as a result of my late-night classic-movie watching. There was nothing I liked more than a quiet house after all had gone to bed, homework abandoned beside me, a sandwich made from leftovers in my lap, and staying up way too long with my gang from the Great Golden Age of Film.

So when decades later, I finally, finally, began to think seriously about writing that book I thought was in me, I never considered committing my crimes anywhere but in the past.

There are distinct advantages.

History never changes. When you write historical mysteries, you don’t have to worry about whether those details that give your story the texture of reality will make the book feel outdated a mere decade after it’s published.

Phones will always be dialed, and they will have cords. Messages will be left with people who write them down. Long distance calls will be made through an operator, and there will always be the chance that it could take hours and the operator will have to call you back when the connection is finally made.

Typewriters will always be manual, and usually they will weigh a lot! At least 15 lbs. Copies are made via carbons, mimeograph, and Photostat.

Photos are taken with cameras that do nothing but take pictures, and those have to be “developed”.

Shoulder pads will be fashionable. Men and women will wear hats. Women will have gloves on their hands and girdles round their rumps unless the occasion is appropriate for “sports wear”. They will wear floor-length gowns for dancing at nightclubs, where live bands will play.

They will listen to the radio for at-home entertainment, but go to a theater to see movies. And the most popular stars in America will as likely be women as men.

Low tech/high drama. It’s easier to get Lauren, my amateur sleuth, into danger, even to the point of having to confront a killer. Help is not a cell phone call away. Even if she can find a phone, there’s no 911. She’ll either have to know the number of the nearest police substation, or dial 0 and ask the operator to connect her.

She might have to deal with a skeptical desk sergeant or dispatcher. If the address is hard to find, or she isn’t sure exactly where she is, there will never be GPS to help. Prowl-car cops have to rely on knowledge of the area and maps.

Criminal records will always be on paper and kept in file folders in cabinets and dusty basements. Local police will have a hard time finding records in their own city. The urgent manhunt in No Broken Hearts is only possible because in 1947, if a fugitive crossed state lines, your chances of ever finding him dropped radically. Without central databases and the ability to quickly, clearly communicate with other police departments, a suspect could take a new name and simply disappear.

Corruption is a good thing. The cops in 1940s Los Angeles were notoriously corrupt. In the late 1930s, a bunch of them tried to blow up a private detective named Harry Raymond, who’d been hired by a local citizen to look into police corruption – fortunately, most of the blast blew out and up, rather than into the car.

Today, we’d be less inclined to believe that an upper middle class woman would be afraid to go to the police. But Lauren has discovered how deep the corruption goes, and it’s much easier to justify her not trusting the police and having to take things into her own hands.

There are challenges to writing in the past. The biggest, of course, is getting it right.

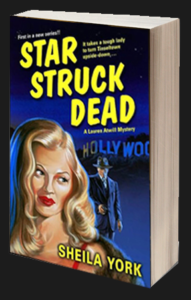

My advice would be to doubt everything you think you know. In a draft of my first book, Star Struck Dead, I blithely wrote a scene in which my private detective, Peter Winslow, tries to persuade Lauren that the class gulf between them is too great for them to fall in love. He’s “from the wrong side of the tracks in about every way you can imagine,” he says. Her snappy – and tongue-in-cheek – reply: “Geez, Winslow, what happened to all those innocent men with only you between them and the slammer?” Except . . . I discovered (fortunately before publication) that “slammer” was not widely used slang for prison till the 1950s.

Yow.

And you have to decide how and where to sprinkle details so your story doesn’t stop for a history lesson or for that “show-off” moment where the author demonstrates how much work she’s done.

In my first draft of any book, I always have way too much detail – to which I subsequently take a machete – and bits in brackets: “[Look this up]”. In the end, a small percentage of what you know ends up on the page.

And all those stars are shining

Oooo, is it tempting to mix real people into a book. Hollywood in the 1940s is full of marvelous stars, with strong personalities. Some beloved, some with scandalous secrets. Some both. You have Hollywood legends both in front of and behind the camera.

Just look at those faces. How could you resist putting that “reality” into your story?

Then you wipe the stardust out of your eyes. Readers will rightfully expect more than a drop-in appearance. That’s lazy writing otherwise, and it gets old fast. And if celebrities are featured characters, you would have to pick them carefully. Once upon a time, when a person died, they were pretty much fair game. Not anymore, with image licensing and estate ownership long after death.

An even bigger issue: you are forever bound by what happens to them. If they would have been filming in Mexico during the weeks in which your story takes place or in Paris giving birth to an illegitimate child, they can’t be in your book.

Early on when I was writing Death in Her Face, I knew I needed a gangster, a truly dangerous man, and I wanted him to be a continuing character. There were too many delicious possibilities in a violent man for whom Lauren would inadvertently do a favor by finding the killer of someone he cared about.

I had to decide, Do I pick a real gangster? There was one who fit the bill rather nicely. No, not Mickey Cohen, who is probably the best known among post-war Los Angeles thugs.

Jack Dragna. He even had a perfect name! He was an extremely powerful crime boss in LA in the 1940s. He was rumored to have “disappeared” his boss. He had dozens of others killed. But I think it’s important to find something to admire in your villains. What if I never found anything in the real man to admire? And frankly, I liked the way my gangster looked in my imagination better than Dragna had in real life.

So Julius (“Julie”) Scarza is Dragna, my way. We are, after all, writing historical fiction.